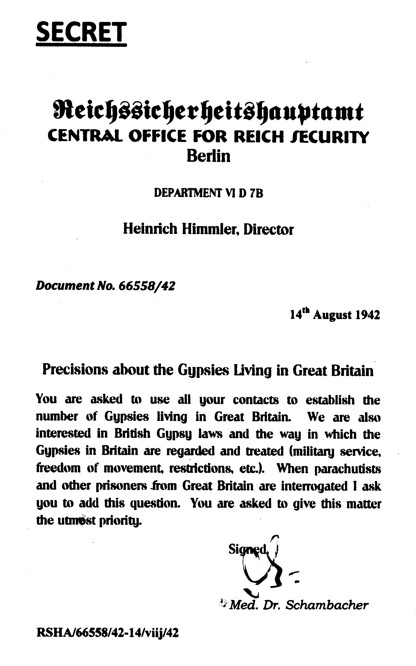

On August 14th, 1942, Heinrich Himmler, the chief architect of the Holocaust, issued a bulletin from the Central Office of Reich Security in Berlin, entitled Precisions about the Gypsies living in Great Britain. Expecting victory, he was collecting information about the people he intended to destroy.

But why did he want to exterminate an entire people? While there were several different groups that were persecuted in Nazi-controlled Europe, only two were singled out because of what they were born, and it was only those two who were selected for total destruction: the Romanies and the Jews.

The Nazi genocide, the planned murder of our two peoples, followed the implementation of the Final Solution. In the Romani case, reference to “The Final Solution of the Gypsy Question” was first drafted by Hans Pfundtner of the Reichs Ministry of the Interior in March 1936. The second specific reference was made by Adolf Würth of the Racial Hygiene Research Unit in September, 1937, and then by Himmler in his Decree for Basic Regulations to Resolve the Gypsy Question as Required by the Nature of Race on December 8th, 1938. The Second World War began nearly nine months after that.

SS Officer Perry Broad of the political division at Auschwitz wrote in his memoirs that “it was the will of the all-powerful Führer to have the Gypsies disappear from the face of the earth; the Central Office knew it was Hitler’s aim to wipe out all the Gypsies without exception.” But why did Hitler want to destroy the Romanies, a people who presented no problem numerically, politically, militarily or economically? And why the Jews? He blamed the Jews for many things—claiming that they invented both Communism and Capitalism, that they were plotting to take over the world, that they created decadent literature, music and films—but Romanies were not accused of any of those things; in our own case, the only reason is in Himmler’s reference to “the nature of race.”

Following Germany’s humiliating defeat in the First World War, and its economic woes in the years afterwards, Hitler wanted to rebuild German pride by getting rid of the foreign blood that he blamed for the situation; he believed it contaminated German “racial purity,” weakened German moral fibre, and had to be weeded out. Only by doing so, could the German people take their rightful place as the Master Race—the Herrenvolk—and of all the different kinds of people in Europe, only Romanies and Jews originated from outside it; they began in Asia. It should be added that the very small number of Europe’s Black population had been quietly rounded up and murdered even before WWII began.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, there were no anti-Jewish laws, but very many anti-Romani laws, about which the general public were already well aware. They had been in effect for centuries, and so even more of them being introduced came as no surprise, such as one he introduced right away called “the law for the prevention of hereditarily diseased offspring,” which ordered the sterilisation of certain categories of people, “specifically Gypsies and most of the Germans of black colour.”

When our ancestors first crossed into the West some eight hundred years ago, the Europeans didn’t know who they were. We were called many different things, but the name that stuck was “Egyptians,” where the mistaken label “Gypsies” comes from. They weren’t Christian, they weren’t “white,” they had no country, and they did not want to get too friendly with the locals; because of these factors and more, they were quickly viewed with suspicion, and being powerless were easily blamed for all sorts of things, accused especially of theft, witchcraft, causing poor crops, and even the plague. Laws were soon passed everywhere in Europe, forbidding them from stopping anywhere; an exception was in Romania, where they were kept instead as slaves for over five hundred years. When the overseas colonies were created, different countries got rid of their unwanted Romanies by shipping them off—to north and south America, Africa, and even to India, our original homeland.

It is important to know these early details, in order to understand why Hitler was obsessed with wanting to exterminate our entire people, because German Romaphobia has a very long history—it didn’t just start with Adolf Hitler; the first anti-Romani law was issued in Germany in 1416, and nearly fifty more were passed over the next 350 years.

In 1500, Emperor Maximilian ordered all Romanies to be out of Germany by Easter, or be put to death. Germans who murdered Romanies were protected by this law, which stated that “taking the life of a Gypsy . . . did not act against the policy of the state.”

In 1580, the governments encouraged Romani hunts in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany; in 1652, the townspeople in Bautzen are fined by the local magistrate for doing business with Romanies, who were then arrested if caught stealing food for their families. The mass murder of Romanies took place in 1659 in Neudorf, near Dresden, and in 1661, Elector Johann Georg II of Saxony imposed a fine on any Romani found in his territory. “Romani hunts” were encouraged as a means of exterminating them.

According to a 1709 law in the district of Ober-Rhein, Romanies apprehended for any reason, whether criminal or not, were sent to the galleys or deported, and a year later, Frederick I of Prussia condemned all Romani men to forced labour, the women to be whipped and branded, and their children permanently placed with white families—another way to breed out a people.

In 1714, an order was issued in Mainz sending all Romani men apprehended to the gallows, and requiring the branding and whipping of women and children. Frederick Augustus, Elector of Saxony, ordered the murder of any Romani person resisting arrest.

A significant year was 1721, when the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Charles VI ordered the extermination of all Romanies throughout the entire realm of the Holy Roman Church. Hitler’s plan was not the first.

In 1722 in Frankfurt, Romani parents were branded and deported while their children were taken from them and placed permanently with non-Romani families. During this period, it was a hanging offence in Prussia for all those above the age of eighteen merely to be born Romani. A thousand armed Romanies resisted German soldiers in an organized fight for their freedom; nineteen were arrested at Kaswasser and tortured to death: four were broken on the wheel, three beheaded and the rest shot or stabbed to death.

An edict from King Frederick William I of Prussia from 1725 condemned all Romanies eighteen years or older throughout the land, to be hanged. In the following year, Johann Weissenbruch described the wholesale destruction of a Romani camp in Germany: five were broken on the wheel, eleven were beheaded, and nine hanged. King Charles VI passed a law that any Romani man or boy found in Germany was to be killed instantly, while Romani women and children were to have their ears cut off and be whipped to the nearest foreign border. By 1740, all Romanies caught entering Bohemia, were hanged by decree.

German racist attitudes had become more deeply entrenched by 1783, when Heinrich Grellmann published his book which established our Indian origin; but in it, he claimed that in doing his research he felt a “clear repugnancy, like a biologist dissecting some nauseating, crawling thing in the interests of science.” The Church’s similar attitude was also expressed by the Lutheran minister Martinus Zippel, who wrote that “Gypsies in a well-ordered state in the present day, are like vermin on an animal’s body.”

On September 14th 1888, the German Imperial Ministry of the Interior issued a lengthy order which said, in part, “Any Gypsies roaming about without legal earning, business or profession are to be criminally prosecuted . . . the main duty of the authorities in fighting the Gypsy Plague must be unified cooperation, involving not only the police, but also the heads of community administrations.”

In the early 1890s, the Swabian parliament held a conference on the “Gypsy Scum,” and recommended that the presence of approaching Romanies could be signalled by ringing church bells to warn the villagers. The military was also empowered at the same conference to apprehend and move Romanies on.

In Munich in March, 1899, under the directorship of Alfred Dillman, the Bavarian police created a bureau later named The Central Office for Fighting the Gypsy Nuisance, and a census of all known Romanies in Bavaria was compiled. Citizens were instructed to report all Romani activity to that office. Dillmann’s Gypsy Book, published in 1905, consisted of a long introduction in which we were described as “a pest against which society must unflaggingly defend itself,” a register of all the names compiled by the police and sent to the Central Office, together with individual criminal records, and many pages of “mug shots.”

In February 1906, one Prussian minister instructed the police to “combat the Gypsy nuisance,” and a register was started to keep a record of Romani activity. The increase of anti-Romani terrorism in Germany caused many Romanies to leave for western Europe, including Britain. A policy statement from the House of Commons in Vienna, capital of the Austro-German Alliance, was sent to the Ministers of the Interior, Defence and Justice “concerning measures to reduce and eliminate the Gypsy population.”

In their 1920 book The Eradication of Lives Unworthy of Life, two Germans, psychiatrist Karl Binding and magistrate Alfred Hoche, argued for the killing by euthanasia of those who were “ballast existence,” i.e. whose lives were seen to be simply dead weight within the body of humanity. This included Romanies, who came under their second category: individuals carrying incurable hereditary disease, a genetic (i.e. racial) characteristic. Based on Dillmann, in our case this was “criminality.” The “criminality” listed in Dillmann’s Gypsy Book were overwhelmingly trespassing, and the theft of food.

Requirements were introduced in Baden in 1922 that all Romanies must be photographed and fingerprinted, and have documents completed on them.

In July, 1926, the Bavarian Provincial Criminal Commission passed a law aimed at controlling the “Gypsy Plague;” Romanies were forbidden to travel in family groups or to own firearms, and those over sixteen were liable for incarceration in work camps. Legislation requiring the photographing and fingerprinting of Romanies was introduced in Prussia in 1927, where eight thousand people were processed in this way.

Following April 12th, 1928, Romanies in Germany were placed under permanent police surveillance. Geneticist Professor Hans F. Günther wrote in his book Study of the German Race that “it was the Gypsies who introduced foreign blood into Europe.” One year later, the Munich Bureau’s National Centre jointly established the Division of Romani Affairs with the International Criminology Bureau (Interpol), in Vienna. Working closely together, they enforced restrictions on travel for Romanies without documents, and imposed up to two years’ detention in “rehabilitation camps” upon Romanies sixteen years of age or older.

On January 20th 1933, officials in Burgenland called for the withdrawal of all Romanies’ civil rights, and the introduction of clubbing as a punishment. On July 14th, Hitler’s cabinet passed a law against the propagation of “lives not worthy of life.”

From January 1934 onwards, Romanies were being selected to be sent to camps for processing, which included sterilisation by injection or castration. Camps were established at Dachau, Dieselstrasse, Sachsenhausen, Marzahn and Vennhausen over the next three years. Two laws issued in Nuremburg in July forbade Germans from marrying “Jews, Negroes, and Gypsies.”

Starting on September 15th, 1935, Romanies became subject to the Nuremberg Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, which forbade intermarriage or sexual relationships between Menchen (“humans”) and Untermenchen (“subhumans”); a Nazi Party policy statement read “in Europe generally, only Jews and Gypsies come under consideration as members of an alien people”—i.e. as “subhumans.” Our own people were categorized by percentage of Romani ancestry; if two of our eight great-grandparents were even part-Romani, we had too much “Gypsy blood” to be allowed, later, to live. These criteria were twice as strict as those applying to Jews; if the criteria for determining Jewishness had been applied to Romanies, some 18,000 would have escaped death (18,000 was also the total number of Romanies in Germany at the time). The non-Romani Traveller people called the Jenisch (Yéniche) were also being arrested and processed, in case their blood-line contained some Romani ancestry.

Between June 12th and June 18th, 1938, “Gypsy clean-up week” took place, when hundreds of Romanies throughout Germany and Austria were rounded up, beaten and incarcerated. In Mannworth in Austria, three hundred Romani farmers and vineyard owners were arrested in a single night. Like Kristallnacht later that same year, the open brutality of the Romanies and the Jews by the police, made it clear to the general public that such treatment had official sanction and was okay. A decree dated September 4th forbade Romani children from attending school. On December 8th, Himmler signed a new order based upon the findings of the Office of Racial Hygiene, which had determined that Romani blood was “very dangerous” to German purity. Dr. Tobias Portschy, Area Commander in Styria, wrote in a memorandum to Hitler’s Chancellery that “Gypsies place the purity of the blood of German peasantry in peril,” and recommended mass sterilization as a solution.

In March 1939, instructions for carrying out the order to register and categorize Romanies were issued, which stated that “the aim of the measures taken by the state must be the racial separation once and for all of the Gypsy race from the German nation, then the prevention of racial mixing.” Dr. Johannes Behrendt of the Office of Racial Hygiene issued the statement that “all Gypsies should be treated as hereditarily sick; the only solution is elimination. The aim should therefore be the elimination without hesitation of this defective element in the population.”

At the beginning of 1940, 250 Romani children from Brno in the concentration camp at Buchenwald were herded together and used as guinea pigs for testing the gas Zyklon B, which was later used for mass killings at Auschwitz-Birkenau. This was the first mass genocidal action of the Holocaust.

An ordinance dated February 11th, 1941, forbade Gypsies and “part-Gypsies” from serving in the German army “on the grounds of racial policy.” This was repeated on July 10th the following year. On July 31st, police officer Reinhard Heydrich of the Reich Security Main Office and who had also been entrusted with the details of the “Final Solution,” wrote “The mobile killing squads have received the order to kill all Jews, Gypsies and mental patients.” On the night of December 24th, the death squads shot eight hundred Romani men, women and children at Simferopol, in the Crimea.

On December 16th, 1942, Himmler signed the order dispatching Germany Romanies to Auschwitz, “with no regard to the degree of their racial impurity.”

By 1945, an estimated 75% of all Romanies in Nazi-controlled Europe had been murdered, but not one Romani survivor was called to testify at the War Crimes Trials in Nuremburg. War-crimes reparations have still not been adequately made, and some Holocaust historians continue to deny our place in the Holocaust, and claim that the genocide of our people was not actually a genocide. The US Holocaust Memorial Council in Washington, which has no Romani member, does not allow the word “Holocaust” to be used in connection with our people, who are set aside in the lucky (?) dip bag of “other victims.” One leading Holocaust historian, who wrote that “for the Nazis, the Gypsies were only a minor irritant,” minimized the number of estimated Romani deaths, which he puts at 150,000, Both the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s late senior historian Dr. Sybil Milton, and the independent research of the International Organization for Migration, put the upper number at 1,500,000.

redaktionen@dikko.nu

Att vara en oberoende tidning kostar pengar därför använder vi oss av crowdfunding. Det innebär att människor med små eller stora summor hjälper till att finansiera vår verksamhet. Magasin DIKKOs insamlingen sker via swish: 123 242 83 40 eller bg: 5534-0046

Vill du annonsera eller sponsra, synas eller höras i våra media?

Kontakta oss på redaktionen@dikko.nu eller ring 0768 44 51 61

IBAN: SE19 9500 0099 6042 1813 4395

BIC: NDEASESS