“This nationalist claim of a Roma Nation is not only absurd, it is an internalisation of antigypsyist thought in Europe” (Lee, 2024).

This is dangerously subjective rhetoric; Dora Yates, the late Hon. Sec. of the Gypsy Lore Society organization, Dora Yates, asked in reference to a nationalist movement “except in a fairy tale, could any hope ever have been more fantastic?” (1953:140). Jaroslav Sus (1961) wrote “it would be wrong to try to prevent the progressive decay of Gypsy ethnic unity.” Twelve years later, the former sub-editor of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald, called the notion “romantic twaddle” (1973: 2), and in 1975, Werner Cohn claimed quite bluntly that “the Gypsies have no leaders, no executive committees, no nationalist movement . . . I know of no authenticated case of genuine Gypsy allegiance to political or religious causes” (1973: 66); yet another Gypsy Lore Society member, Matti Salo, observed that “political activists, both those who claim Gypsy identity and those who do not, have attempted to construct a pan-Gypsy identity, dismissing as irrelevant the ethnic categories of the actors themselves” (1977: 2).

THOUGHTS ON THE 18th FEBRUARY ZOOM MEETING

Ian Hancock

“This nationalist claim of a Roma Nation is not only absurd, it is an internalisation of antigypsyist thought in Europe” (Lee, 2024).

This is dangerously subjective rhetoric; Dora Yates, the late Hon. Sec. of the Gypsy Lore Society organization, asked in reference to a nationalist movement “except in a fairy tale, could any hope ever have been more fantastic?” (1953:140). Jaroslav Sus (1961) wrote “it would be wrong to try to prevent the progressive decay of Gypsy ethnic unity.” Twelve years later, the former sub-editor of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald, called the notion “romantic twaddle” (1973: 2), and in 1975, Werner Cohn claimed quite bluntly that “the Gypsies have no leaders, no executive committees, no nationalist movement . . . I know of no authenticated case of genuine Gypsy allegiance to political or religious causes” (1973: 66); yet another Gypsy Lore Society member, Matti Salo, observed that “political activists, both those who claim Gypsy identity and those who do not, have attempted to construct a pan-Gypsy identity, dismissing as irrelevant the ethnic categories of the actors themselves” (1977: 2).

Although the purpose of the meeting was to discuss the statement made by Jonathan Lee, most of it focused on organizational representation. Of our millions, however, we must keep in mind that we are just a few, and that change must come from the bottom up, and not from the top down.

Musaj t’anklel opre o parrudipe le pinrendar, thaj na hulel tele e sherestar.

It was disappointing, although predictable, that some statements were made counter to our goal. I saw “o Franz naj Rom,” “Sinti naj Rom,” . . . We have a lot of work ahead of us.

I did not join the discussion, only because my “political” time is past; I am one of the few still standing that was there at our first Congress in 1971, but now I am in my eighties and my friend is my computer.

O porr si maj zoralo e xanrrestar.

You can see that I like slogans. Here are two more:

Khanchi p’amende biamengo

and

Te na zhanas katar aviljam, sar shaj zhanas kaj zhas angle?

The first refers to non-Romani societies and political organizations that study and administrate us, who talk about us but not to us. Among the demands made at the Rom and Cinti Union’s National Congress, which was held in Mülheim-Ruhr in November, 1990, was the call for “the immediate dissolution of non-Romani organizations who speak for the Roma and who help perpetuate a circumscribed definition of who we are.”

The second is now my main focus: who decides who we are? The slogan of my college was Knowledge is Power; I have on my wall a sign that says Education is Freedom. The more we know about ourselves as a whole people, the better we can talk back, the more confidence we will have to challenge authority.

We must STOP letting others define us, but we MUST be able to define ourselves. We are not there yet, because we don’t know our history, and are losing our language and culture.

The Internet (najis Devlorreske!) came just in time—a diaspora communications media for a diaspora people. Without it, we would not have met today.

Strictly for debate, I offer these (somewhat random) considerations:

Who is Romani?

If all ±14 million of us constitute a Nacija, we are nevertheless a Nacija Huladi—a scattered nation.

That estimate of ±14 million was very unevenly achieved; there are different official censuses country by country, and there are subjective estimates made by enthusiastic activists. The Nazis thought that there were only some two million of us in their Europe, Jan Kochanowski’s estimate was twenty times bigger. If a Kalderash man is asked “how many Romanies do you think live in the United States?,” he’ll tell you how many Kalderasha he thinks there are. Ask a Romanichal the same question, he’ll guess at how many Romanichals. Both are Romani, each sees the other differently. Each will have different criteria for legitimizing that identity.

Will there (should there?) be a central, overarching, non-partisan body to decide that? To award some sort of authorized identity card? Not an attractive thought.

At this point in our history, recognition and legitimacy is at the endani (subgroup) stage; we share commonality with the others in it, but not with those outside of it. What we should be aiming for, is to extend the limits of recognition to accept endania besides our own as legitimate and equal, which means understanding our common history.

There are three “populations” in particular that must be accounted for, before recognizing who actually “qualifies” as Romani:

(a) those who have re-identified as other peoples,

(b) those who are, but who hide it, and

(c) those who are not, but who say they are.

If those who have re-identified (Ashkali, Egyptians) then by self-definition they have disqualified themselves, and while (possibly) collaborating with and supporting a Romani organization, by choice they would not join it (or be eligible to?).

Those who were born into Romani families but were told not to or have chosen not to identify as Romani, deserve our compassion; we all know why this situation exists. As the strength of our own movement gains momentum, I hope that its success will persuade them to reconsider.

Those who are not but say they are, fall into two groups:

(a) those who have no Romani ancestry at all, but who claim to have—usually for “romantic” reasons; the Internet is crowded with them.

And

(b) there are those who already know about a distant Romani ancestor, or who discovered some ancestry in their DNA results and selected it over the Irish, German, Swedish, &c. markers also in there, as their newly-acquired ethnicity of choice.

Should those who are not Romani at all or have not grown up in a Romani community and who are not familiar with inherited Romani values, speak for Romanies, or be considered members of the Romani Nation? There are non-Romani allies that we should absolutely value and work with.

So, what constitutes “authentic” Romani identity? Can one “become” Romani, and can one “stop being” Romani? The answers are No to the first, and Yes to the second, although there is a difference between “stop being”—a conscious choice to leave the Romanija entirely—and “no longer be”—the historical loss of Romani identity through circumstance, for example the extent of unacknowledged “Romani blood” in the general Romanian and other European populations, as well as the Romani element in non-Romani populations such as the Travellers that has been diluted out of existence through marriage over time.

Romani identity is both genetic and sociocultural, and both matter. Speak up if anyone disagrees with any of this.

The genetics are of academic interest to the historians and other scientists, but of crucial importance to the living society, where they manifest themselves in verifiable family descent. Remember: kasko san – not kon san? A newcomerintroducing himself to a town’s Romani community is immediately asked this, in order to determine whether he is perhaps a relative, or perhaps has been blackballed for some reason, or perhaps wants to move his family into the same town, and the phone calls immediately go out around the country to check.

One gadžikano scholar wrote about the concept of “Kalderashocentrism.” His point was that, because the Kalderasha have been the most intensely investigated and written about, they have become “the most Gypsy Gypsies” for the gypsilorists, by whom all other endania are compared.

It is true that because of the centuries of isolation in bondage on the Wallachian and Moldavian estates, the Kalderasha and other Vlax Roma have retained much of the core culture that other endania have lost. The Sinti endani is likewise extremely conservative. Do we rank the different endania on the basis of conservatism? It is true that the stronger the maintenance of the culture, the stronger the use of the language. It can happen that as the core culture and language becomes lost, the world sees “Gypsy” identity as primarily occupational, and even that “Gypsy” culture is a culture of poverty.

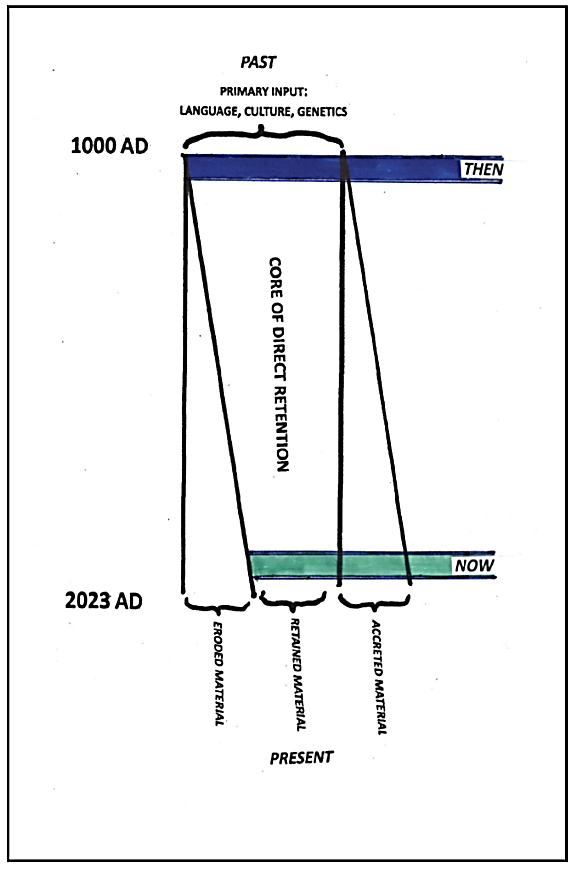

I have included here my “core of direct retention” chart, which diagrams what is lost and what is gained.

The core consists of our language, culture and genetics acquired in the pre-European period (Indian, Dardic, Iranic, Armenian, Georgian, Greek), until the time of the coalescing of the pre-Romani peoples into the Romanies in Anatolia.

Eroded material is what has been lost of the core over time, and it is the diminished core plus the accreted material—everything that has been incorporated since—is what we have today, reflected differently in the different endania.

IT IS THE SHARED, RETAINED ELEMENTS OF THE CORE THAT UNITE US.

IT IS THE ACCRETED ELEMENTS THAT SEPARATE US.

O ilo e Rromanimasko si sava andine amensa zhi ka o astarimos and’e Eropa

de 750-800 bersh: shib, kultura, rat.

Maladjon amen.

E prami kidine datunchara e gazhendar si, so

hulaven amen.

The same is true for the language; some Romani words used in Europe seem not to have made it across the Atlantic with the first Vlax Roma; some families may use amborim but I’ve never heard it here; instead I hear dikhasa.

Accreted material is everywhere far greater than the retained core material. Nearly half (40%) of the words in one Kalderash dictionary are Romanian, not Romani. But keep in mind that only 28% of the words in the Oxford English Dictionary are in fact English; the rest are French, Latin and so on. Since no word for e.g. “television” accompanied our ancestors out of India, we eventually needed a word for it. The Kalderasha here say telivizjono, the Romanichals call it a dikin-mukta. My oft-told “ceiling fan” story is about a compromise using the shared Romani words in a whole phrase to translate it, because Roma from Mexico attending a wedding in Texas called it a bentiladoro (from Spanish) while in American Romani it’s a feno (from English). Other than pointing at it, resorting to Romani worked: le phaka p’o tavono so šudjaren e soba/ so amboldel e balval) because neither family spoke the other country’s language. The development of a standardized, written dialect is a necessity that must be firmly on the agenda: “E dobunda le khetanimaske amara čhibako si o angluno paso karing o khetanipe sar jekh narodo, the achievement of linguistic unity is the first step toward unity as a people.

The genetic component is not fixed, and there are no Romanies anywhere whose ancestry is wholly Indian. Every single one of us has multiple inputs into the family line—which makes us no different from almost every other human population. The extent of non-Romani genetic “mixture” in any Romani population is greater the further north and west it moved after the aresipe. Should this determine “Romaniness”?

While generational descent through the paternal line (and ideally through both sides) is necessary, it is the Sociocultural components that are more important in terms of identity. What about 100% Romani babies adopted and raised by gadže, and never told of their birth-parents’ identity? There are lots of them in the United States.

The core cultural component for all groups concerns hygiene, and specifically, the distinction between being physically unclean (e.g. with dirt) and being spiritually unclean. The latter distinction is rigorously maintained in some endania, and less-so in others. Our “spiritual batteries” (dži) must be kept fully charged and balanced, and this is only achieved by living according to Romanipe(n). Not doing so causes imbalance, bad luck, bad health, prikaza and so on. The non-Romani world, and those who inhabit it, are also “unclean,” and can “pollute” the Romani world. Gadže invited into a Romani home are shown to special chairs set aside just for them, and are offered tea or coffee in cups set aside only for them. Apart from the harsh administrative levels taken to marginalize our people, we too have kept the gadžikanija out of our personal lives because of this; it is both factors, external (racism) and internal (Romanipe), that have kept the barriers in place over the centuries and helped us remain distinct. It is the price we pay to be who we are.

These strict cultural requirements, which involve washing different things, preparing food, dress, &c., can also create barriers amongst our own people. Because of our diaspora, what has been lost of them differs from endani to endani. In my local, mixed Romani community, for example, Kalderash men can never wear shorts; the Romanichal men do; Romanichals take their shoes off coming into the house, Kalderasha don’t. The Machvaya kill a lamb at Easter, the other’s don’t. Newly-arrived Ursaria speak Romani all the time, but are not familiar with many of the customs. But when visiting each other, these different groups have learnt enough about each other traditions to respect and accommodate them. An implicit education.

Education:

I mentioned in an earlier post reviving The Great Romani Encyclopedia, and I’d like to see that plan given new life. It would provide a source for Romanies whose communities have lost many of the core values and behaviours; interested parties from the various endania could be called upon to list all of the traditional customs they are familiar with, and those shared everywhere (and thus not endani-specific) form a go-to template. Fewer than half of our world population speaks any kind of Romani; language classes could be designed which teach the culture and the history at the same time.

Booklets, printed or audiotaped, must be prepared for the vast majority of our people, in whatever dialect they speak, with a parallel text in the yet-to-be devised standard, dealing with civil and human rights, birth control te jertin, using the law, how to protest discrimination and so on.

T’aven baxtale savorrenge,

More later

Devlesa,

o Yanko

Ian Hancock

redaktionen@dikko.nu

Att vara en oberoende tidning kostar pengar därför använder vi oss av crowdfunding. Det innebär att människor med små eller stora summor hjälper till att finansiera vår verksamhet. Magasin DIKKOs insamlingen sker via swish: 123 242 83 40 eller bg: 5534-0046

Vill du annonsera eller sponsra, synas eller höras i våra media?

Kontakta oss på redaktionen@dikko.nu

eller ring 0768 44 51 61

IBAN: SE19 9500 0099 6042 1813 4395

BIC: NDEASESS