DEFEATIST CLAIM: I argue here that calling all Romanies “Roma” is a lazy manipulation of labels that just makes it easier for non-Romanies. I do realise, however, that at this point, using “Romanies” instead is a losing battle. “Roma” seems to be here to stay. Whatever it is, we need one all-encompassing word together with each sub-group’s endonym (self-ascription), thus “I am a Sinti Romani, I am a Romungro Romani, I am a Romanichal Romani” and so on, “Romani” being the unifying word. IFH.

“GIPSEY: A race of vagabonds which infest Europe, Africa and Asia, strolling about and subsisting mostly by theft, robbery and fortune-telling. A reproachful name for a dark complexion. A name of slight reproach to a woman, sometimes implying artifice or cunning.”

Noah Webster, The American Dictionary of the English Language (1828).

“People who can define are masters”

Stokely Carmichael1

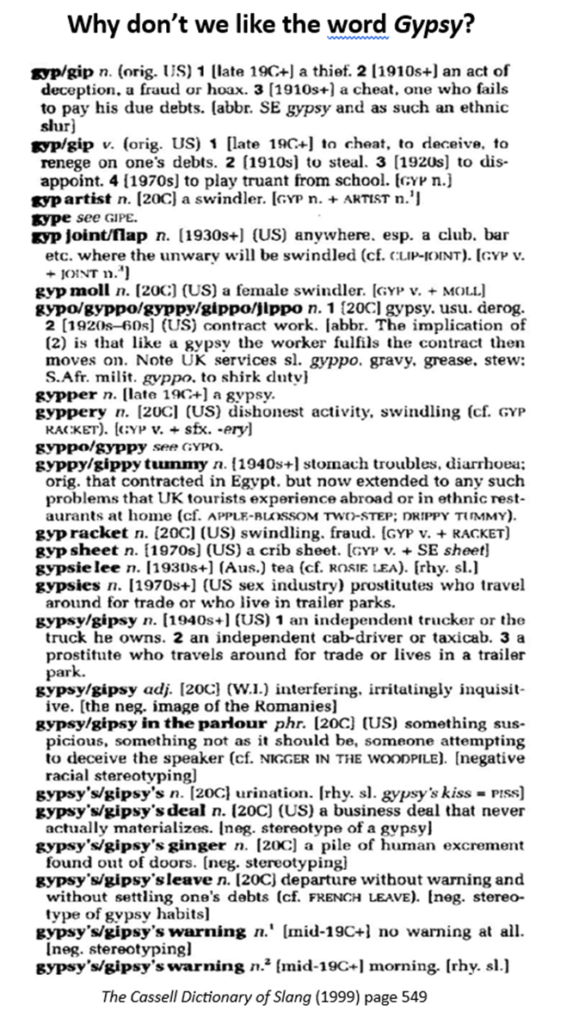

In recent years, objections to the word “Gypsy” have been growing. One argument is that it is a misnomer, since it originates in the word “Egyptian.” But perhaps the greater objection is that it is also applied to socially-defined groups that have nothing at all in common with us or even with each other, except the perceived behaviour of rootlessness or criminality. Thus, there are “gypsy cops,” “gypsy scholars,” “weekend gypsies,” “Broadway gypsies,” “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves” and so on, ži-ka šada’ ma. But there are some who cannot let it (and its equivalents) go. As Jackson says, “definition is itself at the roots of racism—the way we reduce the world to a word, and gag the mouths of others with our labels” (1995: 14). The author of one MA thesis explained “I have decided to use the word Gypsy throughout, although the Gypsies in the United States prefer to be called Rom or Romani [and for whom] ‘Gypsy’ has derogatory connotations . . . However, I felt it best to use the most familiar term” (Meyers, 1987: 3). Another writes “the word ‘Gypsy’ has lost ground to the word ‘Roma’ in texts and discourses by and about Gypsies/Roma [. . . but] in this presentation I prefer ‘Gypsy’ . . . rather than escaping into the more sterile term ‘Roma’” (Fallon, 2002: 1). And more recently, one author writes “‘Gypsy’ is considered a pejorative term . . .so why didn’t I title my book The Rain Rom? Because The Rain Gypsy sounds so much better” (Smith, 2022: ix). The German equivalent too, was defended byGuenther Lewy, who put his stamp of approval on what it is okay to call us, maintaining that “in fact there is nothing pejorative, per se, about the word ‘Zigeuner’” (2000: ix), despite its rejection by both the German Sinti Romanies themselves, and by contemporary German media policy. Easily allowed, when we ourselves say nothing.

So now there is the word “Roma,” which has been seized upon as being an acceptable replacement, at least by some.

I brought attention to this nearly fifty years ago (Hancock, 1975: 47), when I wrote:

While all married Gypsy men may refer to themselves individually as Rom, that is ‘man’ or ‘husband,’ and the root of the word Romani, the Roma as a group are just one of the nations, others being Sinti, and so on. Because the usual word encompassing the entire race is the misnomer ‘Gypsy,’ some speakers are beginning to use Rom(a) in a wider sense as the preferred term.

Agarin (2014: 16) wrote:

[C]onventions are in place to favour “Roma” as the term used in European organisations to denote all members of Traveller, as well as Romani groups. There are groups with traditional and present-day endonyms such as Sinti, Manouches, Romanichal, Kale, etc., who disapprove of “Roma” as the proper term for all Romani groups . .

. . . because not all Romani groups call themselves Roma. Prioritizing those who do over all other groups was also brought to the attention of Yildiz & DeGenova (2018) and Lipphardt (2021), who call it “reifying.”

The decision to use it as the blanket term was not made by us.2 It was made by the European Commission in 2012, when it created the (non-Romani) ‘European Framework of National Roma Inclusion Strategies.’ It stated:

The term ‘Roma’ is used . . . to refer to a number of different groups (such as Roma, Sinti, Kale, Gypsies, Romanichels, Boyash, Ashkali, Egyptians, Yenish, Dom, Lom) and also includes Travellers.3

Subsequently-published official documents now use the same all-encompassing definition for all sorts of non-Romani groups, in the same way that “Gypsy” is. Even the Dom and Lom in the Middle East are being called “Roma.” In July 2003, a Reuters release carried the headline “The Pogrom starts again: Roma-hunting in Iraq,” although the population in question came from Syria, and is Kauli (El-Liethy, 2003).

Central European University professor Gabor Kezdi and doctoral student Eva Suranyi addressed this in their report on education (2009: 9 fn.2):

There is some controversy about the name of the Romani ethnic group. In Central and Eastern Europe the name Roma is used, as a noun (Roma plural) and also as an adjective. It is also used by some international organizations and initiatives, such as the Roma Education Fund or the Decade of Roma Inclusion. The United Nations, the U.S. Library of Congress and other international associations use the Romani name for an adjective and a noun as well (Romanies plural). The name Gypsy is used by many non-Roma but not by the Roma: It is a name created by outsiders and is derived from the misconception of Egyptian origin. Similar to the alternative local names such as Tsigane, Cigany, Gitane or Gitano, the name Gypsy brings negative associations about lifestyle or projects images that are inaccurate for many Roma (e.g. the romantic image of travelers). In this study we use Roma and Romani interchangeably.

In her book on education as a means of combatting racism, Ellie Keen (2015: 10) writes:

The term ‘Roma’ is used throughout this publication to refer to Roma, Sinti, Kale and related groups in Europe, including Travellers and the Eastern groups (Dom and Lom). It should be understood to cover the wide diversity of the groups concerned, including persons who identify themselves as Gypsies. The term ‘Rom’ is also used to refer to a person of Roma origin. Both ‘Roma’ and ‘Romani’ are used as adjectives: a ‘Roma(ni) woman,’‘Roma(ni) communities,’

and Carty & Mirga (2010: 7) have:

In line with OSCE practice, this book uses the term “Roma and Sinti.” The Council of Europe uses the term “Roma and Travellers,” whereas the European Union uses “Roma.” These terms are all-encompassing for other generic terms with which Roma and Sinti are often associated, such as “Gypsies” and derivations of the term “Tsigane.” Where country specific examples are given, the terms used are those particular to the group’s preferred term in the respective country.

Milena Pandy-Szekeres (2022: 4) makes it clear:

Although ‘the Roma’ has increasingly become the accepted umbrella term for a constellation of groups and communities found across Europe, the people who fall under this label are far from homogeneous. [There are] Roma communities that call themselves a variety of names in addition to Roma . . . these autonyms include Sinti (Germany and Austria), Kale (Finland), and Manus (France). In Central and Eastern Europe, Roma is generally the accepted term, even as some communities do not identify with this overarching identity.

Clearly, there is a deal of confusion about what to call us. Columbia University law professor Jack Greenberg wrote (2010: 921 fn. 2) “Commonly called Gypsies, many now choose to be known as Roma or Romanies, a name preferred by official and international agencies. Nevertheless, most contemporary official reports and documents I have seen use Roma. A leading NGO calls itself the Roma Education Fund. I usually use Roma because the Roma groups with which I meet use it.” Which is perfectly fine, if that is how those he meets refer to themselves.

Marushiakova & Popov (2016: 4) have rightly asked “why no other nation in Europe is defined according to its cultural characteristics”? “Traveller,” for example, has nothing to do with ethnicity. Anybody can be a traveller, and if capitalizing the word makes it an ethnicity (an editorial policy usually denied the word ‘Gypsy’),4 then it must apply only to those that actually travel, of whatever actual ethnicity—and those with historically-rooted ethnicity, such as the Irish or Scottish or Welsh Travellers, have their own names for themselves: Minceirs, Nawkins, Kalé.

Not all Jews are Sephardic. Not all First Nations people are Navahos, but so far, only the Sinti Romanies have been successful in insisting that they be called by the name they call themselves—despite which, one announcement read “Roma MP in European Parliament starts his speech with words I am Sinto,” and the English translation of the most recently-published book can still tell its readers that the Sinti are a kind of Roma:

The term Roma has been used to describe real-life individuals and the group as a whole, whereas Sinti designates the German-speaking subset thereof (Bogdal 2023: 5).

There is now a project in Germany to create an encyclopedia of the Holocaust of the “Sinti and Roma.” Not only is there not a single Holocaust scholar that is a Romani person him or herself, involved in that project, but by definition Kalé, Romanichals, &c. are excluded, since their own endonyms (self-names) are neither “Sinti” nor “Roma.” Along with the periodicals Romani Studies and Critical Romani Studies, there is now the Spanish International Journal of Roma Studies. Another new Spanish publication, initially known as the Journal of Gypsy Studies, has recently renamed itself more pointedly as Discrimination.

Someone who recognizes that the Roma endani is just one of the many is Jonathan Lee, a British Romanichal and Advocacy and, surprisingly, Communications Director for the European Roma Rights Centre; he wrote (2014: 1):

the word Gypsy (an exonym only used as a self-identifier by some Romani people), [is replaced by] Roma (a group of some Romani people from Central and Eastern Europe) to encompass a plethora of peoples who share a distant common ancestry.

His argument, however, is not the imprecision of the word, but the intent behind its application in the concept of a Roma Nation:

The Roma Nation ideologically takes Romani people out of their native countries’ political environment. Rather than demanding equitable access to their rights as equal citizens of their own country, they are told to seek it elsewhere in an ethereal nation ruled over by a traditionally conservative elite of old men in stiff, shabby suits. This nationalist claim of a Roma Nation is not only absurd, it is an internalisation of antigypsyist thought in Europe.

This is dangerously subjective rhetoric; Dora Yates, the late Hon. Sec. of the Gypsy Lore Society organization, Dora Yates, asked in reference to a nationalist movement “except in a fairy tale, could any hope ever have been more fantastic?” (1953:140). Jaroslav Sus (1961) wrote “it would be wrong to try to prevent the progressive decay of Gypsy ethnic unity.” Twelve years later, the former sub-editor of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald, called the notion “romantic twaddle” (1973: 2), and in 1975, Werner Cohn claimed quite bluntly that “the Gypsies have no leaders, no executive committees, no nationalist movement . . . I know of no authenticated case of genuine Gypsy allegiance to political or religious causes” (1973: 66); yet another Gypsy Lore Society member, Matti Salo, observed that “political activists, both those who claim Gypsy identity and those who do not, have attempted to construct a pan-Gypsy identity, dismissing as irrelevant the ethnic categories of the actors themselves” (1977: 2).

Following established usage, especially in British publications, the adjective Romani can easily replace Roma in the same way that we refer to “the French,” “the Dutch,” “the Chinese,” &c. Thus “the Romani language,” “a Romani woman.” And, as a plural noun, “the Romanies.” The adjective exists in the dialects of all Romani groups; while a Sinti person will say “I am not a Roma,” he will certainly say “I dress in the Romani way,” or “I am a Romani man.”5

To be clear: the word Roma is either (1) with initial syllable stress, the plural masculine subject case noun meaning only “men.” In the object case, in the singular it is Romes and in the plural Romen, and (2)with final stress, the singular masculine vocative case noun meaning only “Hey, Romani man!” The plural of which is Romale, “Hey, Romani men!” (the slogan Opre Roma thus encourages just one person).6

Roma is not an adjective.

Roma is not a feminine noun.

Roma is nota singular noun.

And it does not apply to all Romanies.

In sum, it is a Lazy Label, one that certainly makes life easier for those in charge of us—a lazy as well as a disrespectful term of convenience for the non-Romani administrators and others who write about us, and who are evidently still confused—or can’t be bothered—about the complexity of who we are. ‘Roma’ means married men, who were once the unmarried čhave.

The Chinese say that the beginning of wisdom is to call something by its right name. Let’s start referring to “the Romanies,” so that we can all join in. We are all Romanies, but we are not all Roma.

_____________

1From a talk given at Morgan State College, Baltimore, January 16th, 196

2How different is this from the creation of a “most successful” award, and then the creators themselves awarding it to themselves? On the decision that the word “Holocaust” should only apply to those who made that decision in the first place?

3Romanipe(n), Romani core-culture, requires a strict social separation between Romanies and non-Romanies (gadže, gawjas, payos, dasa, gore, xale, gomi &c.) based inter alia on the condition of internal spiritual purity, separate from the everyday ritualized practices of hygiene common to all travelling peoples. Conservative populations such as the Kalderash and the Sinti maintain this rigorously, while in countries where there has been intermarriage between Romani and non-Romani groups it has been gradually weakened, along with the loss of the Romani language.

4In her book on Gypsy identity, Frances Timbers writes “I have chosen to employ the term gypsy in the lower case to follow the historical application of the designation” (2016: 16), after stating on the previous page that “[t]he modern application of Roma was adopted at the first World Romani Congress in 1971 to designate the various groups, including the group previously known as gypsies in England.” The policy was rather to cease referring to the various groups by their exonyms (“gypsies,” “gitanos,” Zigeuner,” “Tattare,” Cikan,” &c.) and to refer to each by its self-applied endonym.

5The Balkan Romani word endani is applicable to the various “sub-groups” that make up our total number, preferable to the often used and exoticizing word “tribes.” the Sinti, the Roma, the Kale, the Manuš, the Romanichals, the Romungre, the Xoraxaja and others are all among the different endanja, and the word would usefully be incorporated more widely into the dialogue.

6Another grammatical misinterpretation is the use of the adverb Romanes for the noun Romani

To refer to the language; vrakerav Romanes means “I speak in the Romani way,” not “I speak Romani.”

Works referenced

- Agarin, Timofey, 2014. When Stereotype Meets Prejudice: Antitziganism in European

- Societies. Stuttgart: Ibidem Press.

- Bogdal, Klaus-Michael, 2023. Europe and the Roma: A History of Fascination and Fear.

- London: Penguin Random House.

- Carty, Kevin & Andrzej Mirga, eds., 2010. Police and Roma and Sinti: Good Practices in

- Building Trust and Understanding. Vienna: Strategic Police Matters Office Publication

- Vol. 9. ODIHR: Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

- Cohn, Werner, 1973. The Gypsies. Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley Publn. Co.

- El-Liethy, Imam, 2003. “Iraq’s Gypsies struggle for life after Saddam’s fall,” Islam on

- Line, Baghdad, May 6th.

- Fallon, David, 2001. “Gypsy political effort in post-communist Europe,” at

- http://www.yourwords.com/fallond/325.html.

- Greenberg, Jack, 2010. “Report on Roma education today: from slavery to segregation and beyond,”

- Columbia Law Review 110(4): 919-1001.

- Hancock, Ian, 1975. “Some contemporary aspects of Gypsies and Gypsy nationalism,”

- Roma 1(2): 46-55.

- Jackson, M., 1995. A Home in the World. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Keen, Ellie, 2015. Mirrors: Manual on Combating anti-Gypsyism through Human Rights

- Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Lewy, Guenther, 2000. The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies. Oxford University Press.

- Kezdi Gabor & Suranyi Eva, 2009. “A Successful School Integration Program,” Roma

- Education Fund, Working Paper No. 2.

- Lee, Jonathan, 2014. “There is no Roma nation,” The Norwich Radical, January 31st, p. 1.

- Lewy, Guenther, 2000. The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies. Oxford University Press.

- Lipphardt, V. (2021). “Europe’s Roma people are vulnerable to poor practice in genetics,”

- Nature 599: 368-371.

- Marushiakova, Elena & Vesselin Popov, 2016. Gypsies in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

- Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Meyers, Anat Elizabeth, 1987. The Gypsy as Child Stealer: Stereotype in American Literature.

- Master of Arts thesis, The University of California, Berkeley.

- Pandy-Szekeres, Milena J., 2022. A ‘Truly European Language:’ Europeanization and

- Supranational Language Regimes in the Case of the Romani Language, 1998-2018. Doctoral thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Toronto.

- Salo, Matti, 1975. “Gypsy ethnicity: implications of native categories and interaction for

- ethnic classification,” Paper presented at the Southern Anthropological Society meeting, Clearwater Beach, FL.

- Smith, Susan A., 2022. The Rain Gypsy. High Bentham: Conrad Press.

- Sus, Jaroslav, 1961. Cikanska Otazka v. ČSSR, Prague.

- Timbers, Frances, 2016. ‘The Damned Fraternitie’: Constructing Gypsy Identity in Early

- Modern England, 1500-1700. London: Routledge.

- Vesey-Fitzgerald, Brian, 1973. “Romany nationalism?” The Birmingham Post, July 14th.

- Yates, Dora, 1853. My Gypsy Days. London.

- Yildiz, C., & N. De Genova, 2018. “Un/Free mobility: Roma migrants in the European

- Union,” Identities 24: 425-441.

Läs även

Irländska resande är inte besläktade med resande/romer. De har olika DNA fastslår forskningen.

redaktionen@dikko.nu

Att vara en oberoende tidning kostar pengar därför använder vi oss av crowdfunding. Det innebär att människor med små eller stora summor hjälper till att finansiera vår verksamhet. Magasin DIKKOs insamlingen sker via swish: 123 242 83 40 eller bg: 5534-0046

Vill du annonsera eller sponsra, synas eller höras i våra media?

Kontakta oss på redaktionen@dikko.nu

eller ring 0768 44 51 61

IBAN: SE19 9500 0099 6042 1813 4395

BIC: NDEASESS